Native plants and the future of our drinking water

Native plants are part of a collective solution to the expanding problem of stormwater mitigation in Philadelphia.

Climate change and invasive species, however, are affecting their survival. Horticulturalists and scientists say planting native species and understanding their role in water systems can help.

Psst…If you’re like me (not an environmental scientist) and you need a little background, here are a few words that might be helpful to know while reading this article.

- Stormwater: The portion of precipitation that flows over land into storm sewers or surface waters.

- Native plant species: A species that is within its known natural range and occurs naturally in a given area or habitat

- Impermeable/impervious surfaces: a surface through which little or no water will move due to lack of pore space

- Biodiversity: Short for biological diversity. A measure of variation (the number of different varieties) amongst living things.

Source: Oxford Dictionary of Environment and Conservation

Philly’s Location and Build

Penn State Extension’s Penn State Extension Master Watershed Steward Coordinator and Natural Resources Educator Beth Yount said that Philadelphia’s location and build mean that stormwater is “critically important” in her work.

Philadelphia’s drinking water supply, which comes from the city’s Delaware and Schuylkill rivers, actually starts in upstate New York and passes through several states before getting to Philly. “We are almost at the exit point where it goes into the Delaware Bay and into the Atlantic Ocean,” said Yount.

Water cleanup in Philly is an intense process of removing the cumulative pollutants picked up as the water traveled through those communities before reaching the city.

Philadelphia is also a densely populated city covered in about 54% impervious surfaces. Stormwater rolls off these surfaces and directly into the rivers, taking any trash, chemicals, or even animal waste left on the sidewalks.

That’s where native plant life comes in.

Native plants= Natural water filtration

Green spaces create permeable surfaces in which stormwater can be absorbed. But in a place like Philly, which has a “small footprint” in terms of land area, “everywhere that we have green space needs to really be heavy lifting,” explained Yount.

Native plants can be heavy lifters because they increase the biodiversity of a space. They exhibit more diverse plant architecture to filter water in varying ways and have evolved to interact with other local organisms.

“It’s really complex. Grassy things (like grasses and sedges) do a better job of taking out those sediments, capturing them. Woody things (like shrubs and trees) slow down the flow. And then you have microbial life that evolved to work with these plants and break down pollutants biologically.”

On the contrary, non-native species—for instance, popular European turf grasses—do not interact as intricately with the local flora and fauna.

For these and even more reasons, city developers are turning to native plant life. For instance, FDR Park’s major redevelopment plan includes the restoration of native species. 8,880 have been planted, out of a total 44,198 native plants planned according to the Philadelphia International Airport spokesperson Heather Redfern.

Still, there are concerns for native plant species’ survival.

Plants on the move

Climate change and invasive species threaten the existence of native plant species. Invasive species are invasive because they thrive well in the environment and have no natural competitors, the National Wildlife Federation explains.

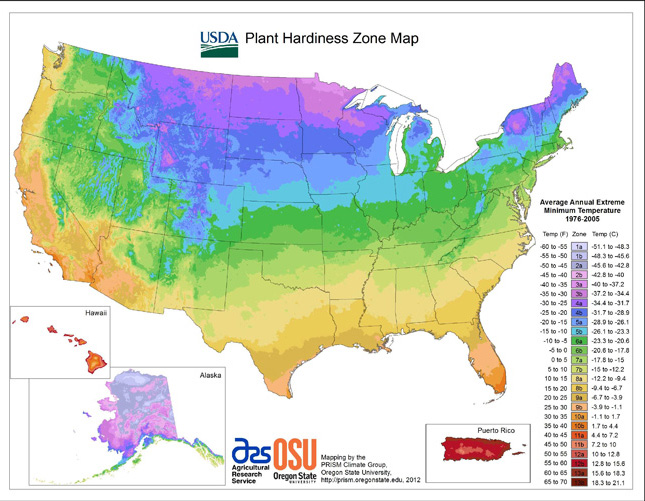

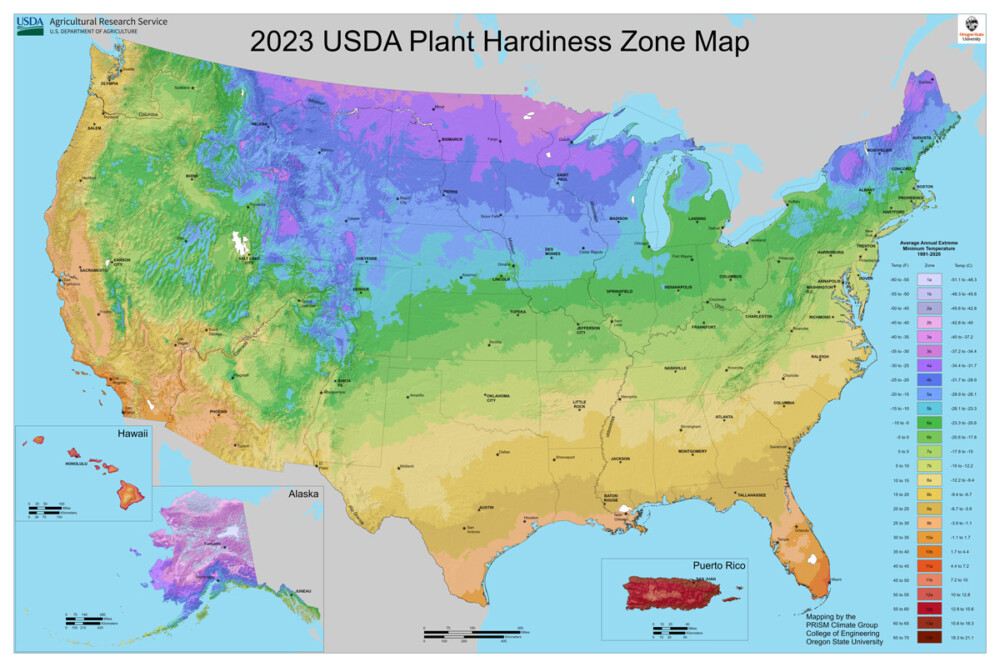

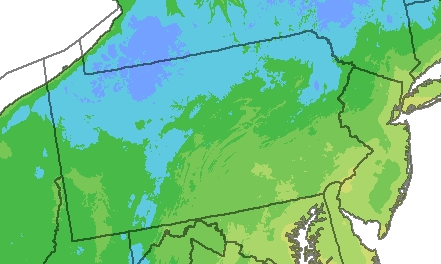

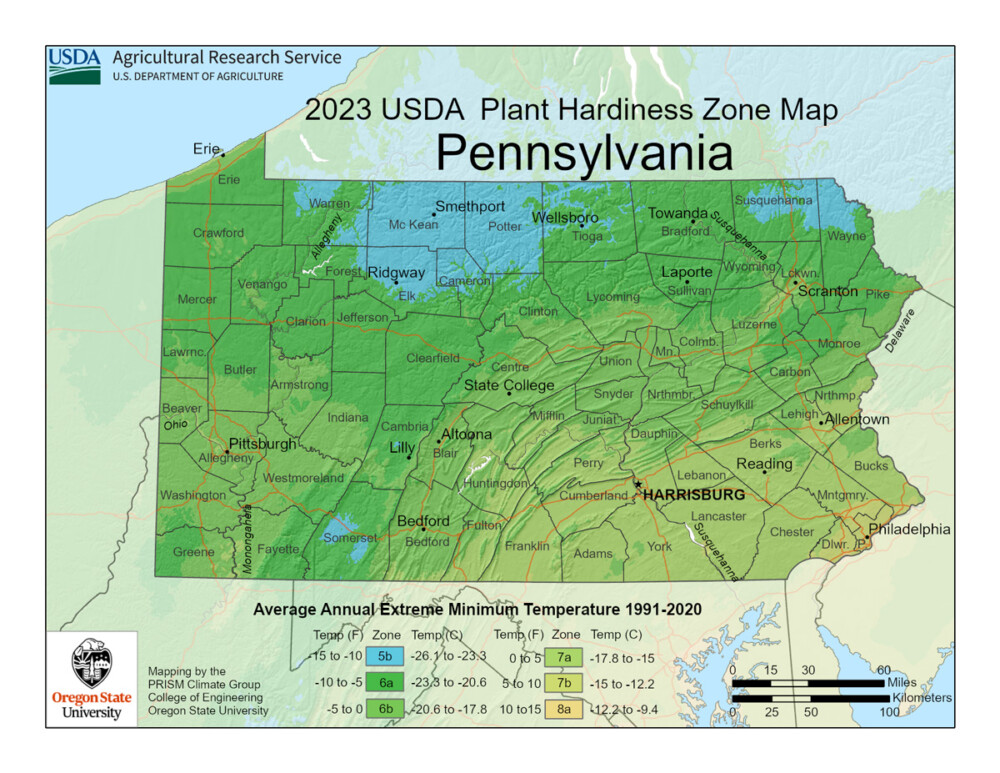

Native plants also face major climate changes. At the end of 2023, the USDA released a new Plant Hardiness Zone Map, illustrating Pennsylvania’s warming climate compared to the previous 2012 map. Colder climate plants must migrate north to keep up with the changes.

“We think that plants are moving at about 13 miles every decade,” said Beth Yount.

Biologists in the near future may consider using plants from a specific part of their growing region – called provenances – to increase their chance of survival up north, according to Andrew Bunting, Vice President of Horticulture at the Pennsylvania Horticultural Society (PHS).

Bunting used the red maple tree as an example.

“Red maple has a range from Canada to southern Florida. If you planted a red maple in Florida from its northern provenance, it’s probably not going to do well,” he said.

“However, say you got red maple seed that’s growing currently in North Carolina. In theory, embedded in the genes of that plant will probably be greater heat tolerance, maybe greater acclimation to humidity.”

That means the red maples would “theoretically do better” in Philly during the hotter, humid summers as climate change heats the region.

What YOU can do: Native rain gardens

When it comes to stormwater management, there are many ways we can participate—or not. “There are things we can avoid, like being cautious of what we put on our lawns, and then there are positive things to add and integrate,” said Yount.

One such option is a native rain garden to soak up stormwater and encourage local biodiversity.

Rain Check is a program funded by the Philadelphia Water Department and managed by PHS that provides Philadelphia property owners with stormwater management tools. Rain Check provides contractors who work with homeowners to design and install rain gardens.

“Don’t just steer clear of the wet parts of your lawn,” said Bunting. “See it as an opportunity to turn it into a rain garden.”

Bunting suggested planting species that can be in standing water for 24 hours. He also suggested choosing plants that are faster to mature–like the summersweet with its “fragrant flowers”–so that gardeners can see the fruits of their labor earlier.

Penn State Extension offered a free Choose Native Mini Workshop online on April 16th at 6 pm for property owners, landscapers, and those interested in learning more about native plants in Pennsylvania.

Concluded Yount about environmental work: “We silo too many things. It’s really just a matter of understanding things as a system and as communities.”

Additional resource: Keystone plant list for Pennsylvania’s ecoregion.

Cover photo: East Park Greenway Rain Garden

Correction: A previous version listed Beth Yount’s position as simply Master Watershed Steward Coordinator. Yount’s title has been updated for specificity. The link for the Choose Native Mini Workshop has also been updated to the recording of the event.